Meals and Community Membership in Rondo

This exhibit discusses the impact of food on the culture of the Old Rondo neighborhood. Food is an important field of study because it is an unavoidable fact of life for everybody. Simply put, we all have to eat. The ways in which people eat, what they eat, and the customs that surround mealtimes are critical elements of cultures across the globe and Rondo is no exception. This exhibit seeks to demonstrate the importance of food in indicating the cultural and regional heritage of members of Old Rondo’s black community. Additionally, this exhibit notes the power that food had in the Rondo neighborhood to bring people together, and the immense value that mealtimes had in the strengthening of bonds amongst residents. Finally, looking deeper into food production offers a glimpse at some of the gender roles and expectations in Old Rondo.

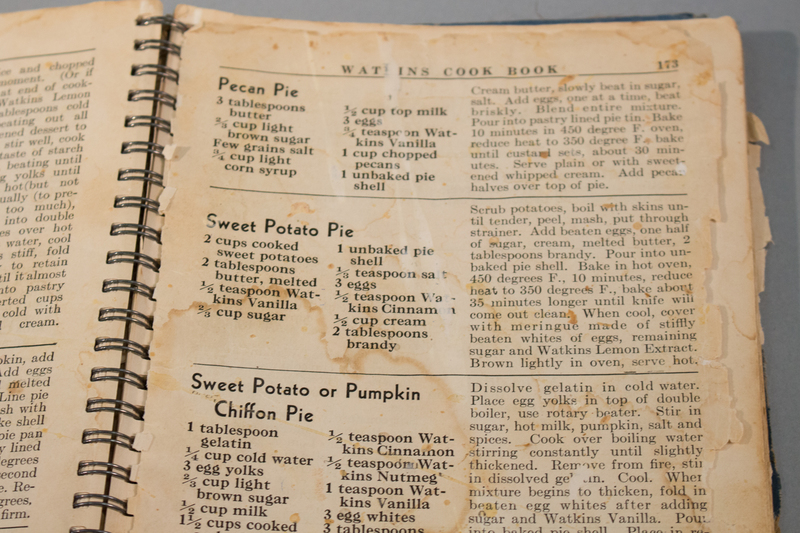

As the text “African Americans in Minnesota” indicates, most African Americans in Minnesota by the 1950s had themselves moved from the South, or were directly descended from parents who had made the transition. In Rondo resident Evelyn Fairbank’s memoir “Days of Rondo”, her own foster mother hails originally from Macon, Georgia. Indeed, Ms. Fairbanks’s stories point directly to the influence of Southern cuisine in Minnesota. Much of the food consumed at Mama’s table had roots in the South, where Mama was born and raised. Two of the foods mentioned by Evelyn are also included in the archive. Both the soup tureen, that Joyce Williams explains was used for collard greens, and the recipe for sweet potato pie harken to some of Fairbanks’s vivid descriptions of the delicacies that poured out of her family’s kitchen. These foods represent cultural and regional heritages that were survived in the cuisine of local residents. These artifacts prove that the story of Rondo is not insulated and independent in the scope of history. The Rondo community is an amalgamation, full of transplanted and adapted cultures that take a unique shape in the heart of St. Paul.

Some of this culture is further revealed by the items in the archive. Food served not only to indicate regional backgrounds, but also played a significant role in the day to day social life of the citizens of Old Rondo. The artifacts in the History Harvest collection help shed light on these practices. First and foremost, eating was a big deal. Food brought people together, and it did so with flair. Evelyn Fairbanks describes decadent picnics on the lawn after church services, during which congregants would bring a massive spread of home cooked delicacies. Mary Boyd too notes the gathering of church picnickers in her own oral testimony. We know therefore that food was immensely important in bringing people together, and the artifacts offer some clues as to the nature of these gatherings. The items of the roasting pan, and the silver teaset give us an impression that eating was meant to be done together. The roasting pan includes the description that it was specifically used for family dinners, and the size of it certainly corroborates this claim. Such a large dish was evidently meant for preparing large quantities of food. Additionally, in Joan Perteet Thompson’s interview, she reveals that her grandmother’s silver teapot was brought out in the presence of guests. These artifacts help illustrate the importance of food in the coming together of Rondo residents.

The items in this collection also provide insight into the nature of these gatherings. Most importantly, as the testimonies of Evelyn Fairbanks make clear, food production was largely the domain of women. In her recollections in “The Days of Rondo” she vividly describes the women busily laboring in church kitchens and at home. Unsurprisingly, all four items in this collection list women as their original owners, and where interviews are present, emphasize the presence of women in their original use. Finally, communal mealtimes were evidently not taken lightly, and were opportunities to show off fancy cookwares as well as culinary prowess. The ornate qualities of the soup tureen and the teapot are testaments to importance of presentation in the company of others. The size and spectacle of mealtime gatherings, combined with the fancy dishware found in the archive also produce another possible conclusion. Food quality and presentation reflected strongly upon its creators, and for many residents--especially women--could have served as a public display of the health and wealth of their households.

Ultimately, the theme of food helps to reveal a few important aspects of culture in Rondo. First, it indicates a regional heritage deliberately kept alive in the community. Second, it shows that food was used as a means to bring together lots of people in social gatherings. When looking at this second conclusion however, there is even more information that can be gleaned. In light of the fact that women owned the role of food producers, large communal gatherings were places that reflected publicly the skills and social position of women and their traditional charge: the well-being of home and household.