Home Ownership in Rondo

In remembering Rondo and recognizing it for its accomplishments and uniqueness, it is imperative to recognize the ways in which home ownership in Rondo allowed the community to flourish. Rondo was unique in that it was a self sustaining and successful black and integrated neighborhood. Home ownership was one of the ways in which community members were able to be self reliant and successful, independently from other places in St. Paul. During the days of Rondo, housing discrimination made black neighborhoods with high ownership rates uncommon. were uncommon. This section draws upon three artifacts to deconstruct the government’s conception that Rondo was not worthy of saving from highway construction, displaying Rondo as a place where home ownership allowed residents to have power over their own neighborhood, creating an independent and thriving community.

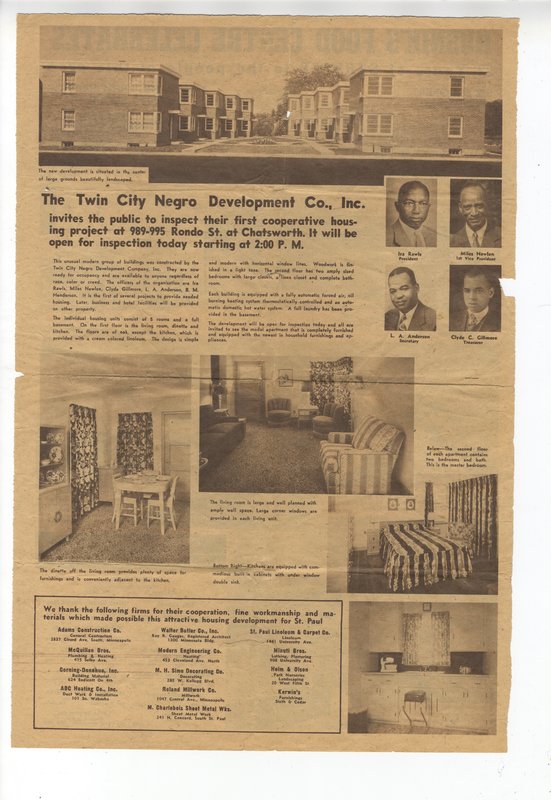

Marvin Anderson’s artifact of a newspaper clipping of an advertisement for Rangh Court, his father’s apartment buildings, highlights the role of housing in allowing for self sustainability in Rondo. Anderson’s father and mother successfully owned and managed the apartments, and many people lived in them throughout the years. While the people who lived in these apartments did not own their homes, they supported a Rondo family’s business through their housing. With the construction of the freeway, however, the Minnesota Department of Transportation claimed that the buildings were not “built well enough” to deserve a high valuation, causing the state to buy them for a low value and remove them for highway construction. The book, Folklore of the Freeway, by Eric Avila emphasizes the strategic destruction of communities of color through highway construction (1). With the notion that minority neighborhoods are not equally valuable to white ones, during the post WWII urban renewal era, urban planners decided to “coordinate urban highway construction with… slum-clearance programs”, which essentially meant the clearance of poor communities of color. The government’s narrative of Rondo devalues the homes and buildings of the neighborhood, claiming them as worthless. However, homes and housing developments were an important part of Rondo, as they were owned and maintained by community members, allowing Rondo to thrive by supporting itself.

1. Avila, Eric R. The folklore of the freeway: race and revolt in the modernist city. Minneapolis: Univ. of Minnesota Press, 2014, 41.

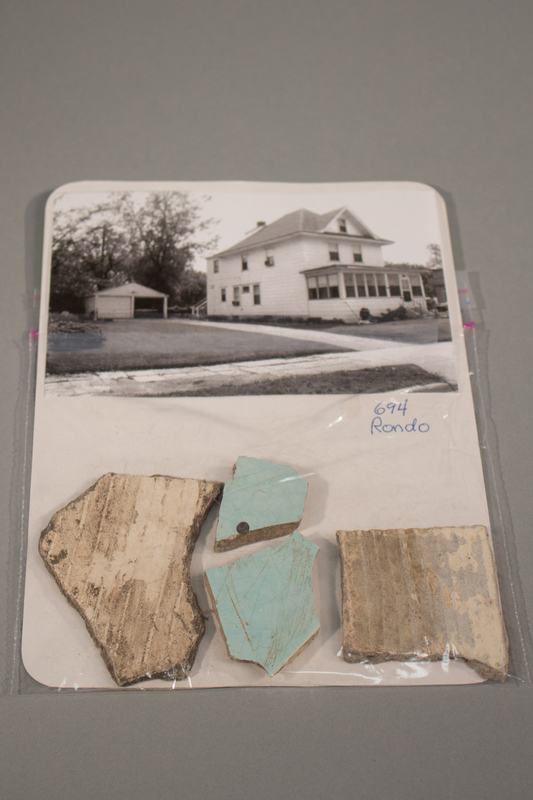

In addition to Rondo-owned housing developments, individual families owned homes, allowing them to accumulate wealth. Margaret Lovejoy’s artifact of remaining pieces of her family’s home after its destruction is an example of both the emotional and tangible value that was lost during highway construction. Lovejoy’s parents were the original owners of their home until it was removed for the highway. Home ownership is a significant way for families to accumulate wealth, and is a path of upward mobility. Throughout American history, housing discrimination against African Americans and other people of color has prevented communities from gaining wealth and being self sufficient, and this remains an issue today. In the book, African Americans in Minnesota, David Vassar Taylor explains that African Americans were forced into the Rondo neighborhood during the late 1800s because of “discrimination and racial antagonism” that forced black communities to move to designated neighborhoods (2). Black people often did not have full rights and freedom over their neighborhoods. However, Rondo was unique in that its members claimed the neighborhood through home ownership, allowing residents to have rights and control over their own community.

2. Taylor, David Vassar. African Americans in Minnesota. St. Paul, MN: Minnesota Historical Society Press, 2002, 14.

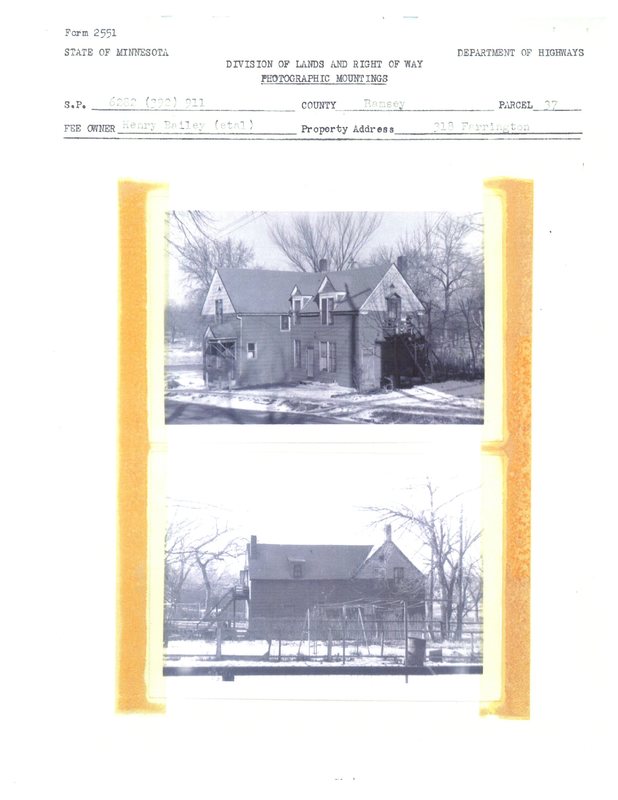

Further, James LaFaye’s artifact of a blueprint of his family’s home before its destruction exemplifies integrated home ownership in Rondo. Given to the family by the State of Minnesota’s Department of Highways, the forms state the homeowner’s name and address of the property. In exchange for their home, the LaFaye family was given these documents and a small monetary sum. The LaFaye family was one of the white families living in Rondo. In a time when most of America remained segregated, Rondo was radical in its racial integration. While Rondo was predominately African American, families of different racial backgrounds lived together in harmony. Due to housing discrimination laws that worked to maintain segregated communities, it was rare for blacks and whites to legally own houses in the same neighborhoods during this time period. As an independent community, Rondo broke the social and legal norms of neighborhood segregation by allowing people of different races to own homes in the same area. In destroying the LaFaye’s home, one of the few places where people of different racial backgrounds were able to live together was demolished.

Home ownership in Rondo enabled the community to have agency over its own neighborhood and increased a sense of community empowerment. What was lost during highway construction was more than physical property, but houses that represented community ownership, self sustainability, integration, and prosperity.